Mitral Valve Disease

Basic Facts

- A healthy mitral valve opens wide to allow blood to flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle and closes tightly as blood is pumped out of the left ventricle to prevent any blood from leaking back.

- Mitral valve disease occurs when the mitral valve is unable to open or close properly and includes mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and mitral valve prolapse.

- Mitral valve disease is generally treated with medicine, unless it is severe. Surgical intervention may be either valve repair or replacement.

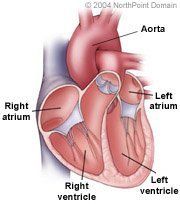

The heart has four valves, two on the right side of the heart, the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, and two valves on the left side of the heart, the mitral and aortic valves. Each valve is made up of flaplike segments or leaflets that open and close so that blood flows through the heart in only one direction. Located on the left side of the heart, the mitral valve is bicuspid, having two cusps or leaflets.

The mitral valve separates the left atrium and left ventricle. When the heart relaxes the mitral valve opens and blood from the left atrium fills the left ventricle. During the heart's contraction, the mitral valve closes, preventing blood from flowing back to the left atrium. A diseased mitral valve no longer opens or closes properly. Common mitral valve problems are mitral valve prolapse, mitral stenosis, and mitral regurgitation.

Mitral valve prolapse, a common condition, is also called the click-murmur syndrome, floppy valve syndrome, or Reid-Barlow's syndrome. With mitral valve prolapse, one or both of the valve's leaflets may be too large, preventing proper closure and allowing blood to leak back to the atrium. Although infrequently serious or symptomatic, it can be associated with serious mitral regurgitation.

Mitral stenosis is the narrowing or obstruction of the mitral valve, which prevents its opening properly and inhibits blood flow from the atrium to the ventricle. The residual blood can increase the pressure in the atrium, causing it to enlarge, which can lead to atrial arrhythmias, or disturbances in the heart's normal rhythm or rate, and edema, or fluid buildup throughout the body.

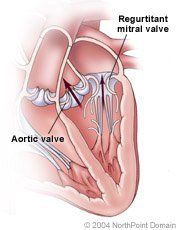

Mitral regurgitation occurs when the valve closes incompletely or improperly during the ventricular contraction, allowing blood to flow from the left ventricle back into the atrium. Mild regurgitation may not cause problems, but as regurgitation persists, the left atrium can enlarge because of increased blood volume. Serious regurgitation can cause the left ventricle to compensate for the blood that leaks into the atrium by enlarging. An enlarged heart can grow weak and begin to fail.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS?

The symptoms of mitral valve disease include:

- Fatigue;

- Shortness of breath;

- Palpitations; and

- Atrial arrhythmias.

As the heart pumps and the aortic valve opens to allow blood into the aorta, a regurgitant mitral valve allows blood to leak backward into the left atrium.

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

Mitral valve prolapse: The causes of mitral valve prolapse are often unknown, but can be caused by Marfan syndrome, a connective tissue disorder.

Mitral Stenosis: The most common cause of mitral stenosis is rheumatic fever, which is an increasingly rare illness in the developed world. The mitral valve is also susceptible to damage from and to the buildup of calcium deposits on and around the valve. Less commonly, mitral stenosis can be congenital, or caused by a malformation that was present at birth.

Mitral regurgitation: Mitral regurgitation may have many causes, including:

- Heart attack;

- Severe ischemia (lack of blood flow to the heart);

- Endocarditis (infection of the heart);

- Hypertension (high blood pressure);

- Traumatic injury;

- Age; and

- Rheumatic fever.

DIAGNOSIS

During a physical exam, a physician may detect heart murmurs, or sounds of abnormal valve function or blood flow through the heart. The physician typically confirms the diagnosis by ordering tests, including:

- Echocardiography (which uses sound waves to produce an image of the heart on a monitor); Electrocardiogram; X ray; Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI); and

- Cardiac catheterization and angiography (in which a physician inserts a thin tube called a catheter into an artery in the leg or arm and threads it to the heart). The physician can then measure the pressure inside the heart, the size of the mitral valve opening, and how much blood the heart pumps. The physician can also inject contrast dye through the catheter to produce an angiogram, a specialized x ray of the valves.

TREATMENT APPROACH

People with mild or moderate mitral valve disease, including mitral valve prolapse, may require no treatment for the condition itself. However, people with valve disease must take antibiotics before and after dental procedures, because bacteria from the mouth can enter the bloodstream and cause infection in the heart muscle that can worsen valve disease. Severe cases of mitral valve disease can be treated by surgical procedures, such as:

- Balloon valvuloplasty (a balloon-tipped catheter treats mitral stenosis by widening the valve flaps); and

- Valve repair; and

- Valve replacement surgery.

Copyright © 2017 NorthPoint Domain, Inc. All rights reserved.

This material cannot be reproduced in digital or printed form without the express consent of NorthPoint Domain, Inc. Unauthorized copying or distribution of NorthPoint Domain's Content is an infringement of the copyright holder's rights.